Projects Newsletters Personnel Contact

Suleyman I was probably the greatest Sultan of the Ottoman empire ( which ruled from Istanbul during the period from 1453 through the mid 16th century) and extended the boundaries of the Ottoman empire to their greatest hegemony.

Under Suleyman I, Turkish fleets appeared in the Western Mediterranean and were feared greatly, due to attacks on Venice, Southern Italy, Corsica and Sicily. Rhodes, North Africa, Asia Minor, Egypt and parts of Persia were added to the empire.

Sulleyman’s greatest achievements however, were in organization and administration. He recognized and incorporated into his administration talent in every type of vacation.

He revamped the legal system personally, earning the nickname ‘Sulleyman the Lawgiver’, and saw to it that the laws were fairly enforced. In this respect, his reign was very similar to that of Justinian a thousand years earlier, under Byzantine rule of the city under its name at that time: Constantinople.

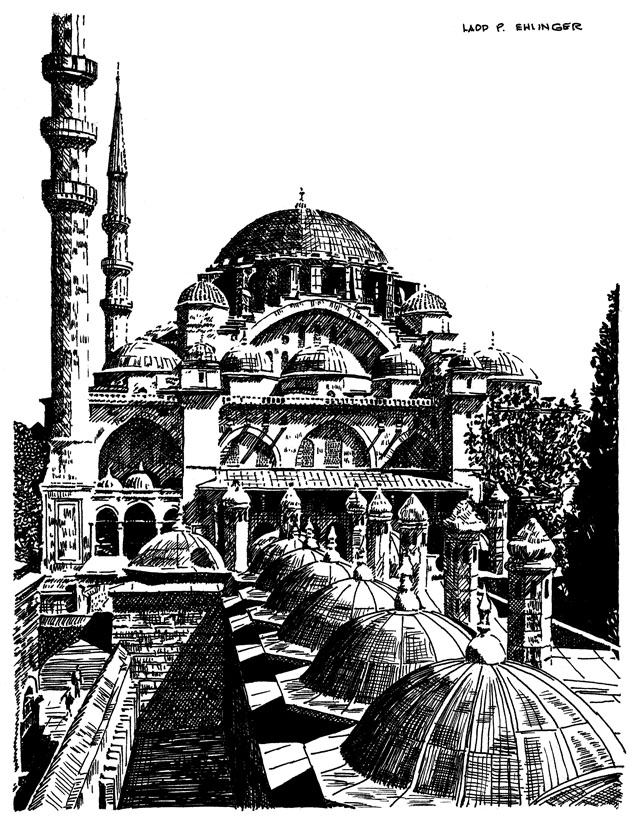

Part of Suleyman’s recognition of talent was embodied in his appointment of and his order to his court architect Koca Sinan to design a mosque that would surpass Justinian’s majestic church, Hagia Sophia. The complex of buildings that resulted was the Kulliye (Mosque with other buildings) of Suleyman, this issue’s limited edition signed print by Ladd P. Ehlinger.

Sinan’s origins and birth date are rather murky. Most historians believe that he was born in 1491, somewhere in Albania or Serbia, of Greek descent (non-moslem). How he arrived in Istanbul is a mystery, as is the term of his life, as the Islamic lunar year was used, which is shorter than the Christian calendar.

From Sinan’s autobiography we do know that he was a soldier, a military engineer, and participated in many Turkish campaigns, gaining much experience building castles, fortifications and bridges. In 1539 he was made chief of the Ottoman Empire’s corps of architects. His campaigns had also given him first hand knowledge of architecture in the Balkans and other countries. If we can believe his derived birth date, Sinan began the practice of architecture as an independent profession at age 50.

Islamic architecture developed slowly over a few centuries and is the product of many places and peoples. It has a limited repertoire of forms and elements that it employs: Courts, arcades, domed spaces and very large portals. It is fundamentally centered upon God, but in a different way from Christian architecture.

At its heart is the mosque, and inward-looking building whose prime purpose is contemplation and prayer. It is a space removed from the immediate impact of worldly affairs. It is not, however, designed to be spiritually uplifting, nor to produce a sense of exhaltation, and there is no positive object of attention or of adoration. Sir Bannister Fletcher’s History of Architecture states: “Above all things the mosque is essentially democratic; in it all have equal rights, and it may sere many functions other than prayer. It is still commonly used as a school, transactions may be made there and treasures stored. Official notices are given out there and newly arrived caravans normally repaired to the mosque where travellers have the right of shelter: and though many of these functions have become comparatively unimportant in modern society, the mosque remains the focus of Moslem life - something between a forum and a prayer house.”

In the Suleymaniye Mosque, Sinan set out to prove to the world that he and Suleyman could surpass the Greeks in concurrence with Sulleyman’s order. The building became one of the most important buildings in Turkish and Islamic architecture and was a turning point in Sinan’s career. Interestingly, Sinan adopted the ground plan of Hagia Sophia, the pinnacle of Greek (Byzantine) architectural achievement. It appears that Sinan did so in an intellectual struggle to solve and surpass the formal problems of Byzantine architecture, which would then free him from those same patterns. The main dome is flanked by two half domes as in Hagia Sophia, but the internal and external expression of the forms and spaces is entirely different.

Hagia Sophia has a continuity of spherical forms and spaces which Suleyman’s Mosque abandons, while articulating the differences with a clarity of structural expression of, rendering a building of great repose and serenity, enhancing its purpose of contemplation and prayer.

The Suleymaniye has a dome with a diameter of 85 feet and a height of 170 feet, surpassing Hagia Sophia. The clarity of structure is enhanced by extensive use of limestone ashlar which is contrasted with intensive decoration and bold modelling based on carefully calculated proportioning. Ceramic tiles are used modestly but with careful precision within the mosque itself and abundantly and brilliantly in the octagonal tombs of the Sultan and his wife Roxlena, in the cemetery immediately behind the prayer chamber.